From Air to Bits: The Complete Path of Digital Audio

If you've ever built an audio pipeline but didn't really understand the underlying physical phenomena, or need a holistic refresher on the subject, this one's for you.

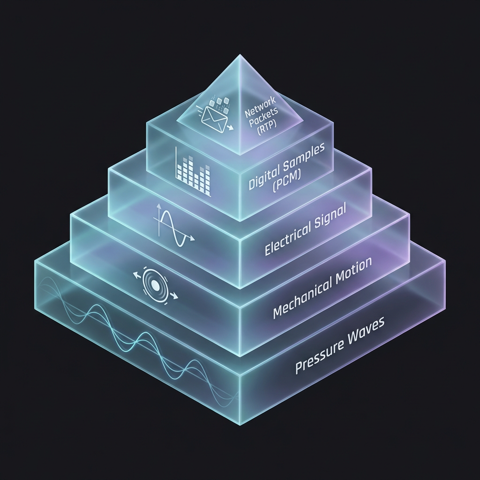

This article will give a high level overview of each level in the pyramid above, aimed at developing an intution for the entire audio lifecycle, following a single sound from the physical phenomena all the way to network packets.

I find it best to learn with a simple example in mind, and a picture is worth a thousand words, so:

A person (source) says "hello world", a mic (sink) picks it up, then converts it to meaningful electrical signals and finally sent across the wire.

Intentionally this is all very hand-wavey, throughout the article we will break it down piecemeal. Note that the example shows the physical/mechanical side only, we will expand on it in later sections.

Sound as Pressure Waves

What we define as sound is really a conglomerate of molecules, driven through some external force at varying densities through a medium; in our case ambient air (≈ 101 kPa) at speed c.

In our example the source speaks "hello world", convertig energy (eg human throat muscle contraction) ito particle excitation. The molecules propagate outwards in the form of a pressure wave through air (≈ 101 kPa).

You can see the behavior these pressure waves exhibit as they permeate through the medium; compressions when air molecules come together and rarefactions when they spread out.

Mathematically, this traversal through ambient air is expressed by the wave equation, shown below in one dimension for simplicity:

If what this second order equation represents isn't immediately obvious, you aren't alone. Essentially, for a given point p, the pressure variation with respect to time t is proportional to how the wave curves in space x around that point.

The speed of Sound

As discussed, the medium on earth is air, and sound moves through it at the speed c:

here is the heat capacity ratio of the gas (~1.4 for air), is the universal gas constant, is temperature in Kelvin, and is the molar mass of air. The key takeaway: sound travels faster in hotter, lighter gases.

Why? Well hotter means more molecular activity, so ease of propagation. Lighter gases follow a similar principle: less inertia, easier to incite motion.

For a simple sinusoidal wave, the speed, frequency, and wavelength are related by:

This is the relationship that connects what you hear (frequency, perceived as pitch) to the physical scale of the wave (wavelength). Some concrete numbers to build intuition:

| Frequency | Wavelength | What it sounds like |

|---|---|---|

| 20 Hz | 17 m | Lowest audible rumble |

| 300 Hz | 1.1 m | Low end of speech |

| 3.4 kHz | 10 cm | Upper range for speech intelligibility |

| 20 kHz | 1.7 cm | Upper limit of human hearing |

The Microphone: Pressure to Motion

So we now understand how sound travels through air a bit more, but how does that get turned into meaningful data? The microphone, of course. It is responsible for receiving the pressure waves and converting them from mechanical vibrations to electrical signals.

there are, of course, many different mic designs; we will focus on a basic mechanism to develop intuition for the device:

The star of the show is the microphone's diaphragm; a thin membrane exposed to air on one side. The incoming pressure variations push the entire membrane in and out — think of a drum skin flexing as sound hits it. The force on the diaphragm is the pressure difference across it, integrated over its area:

The diaphragm itself can be modeled as a damped harmonic oscillator — the classic spring-mass-damper system from physics:

where is the diaphragm's mass, is its stiffness, is damping, and is the driving force from the incoming pressure wave. While you're speaking, the sound wave continuously drives the diaphragm, and it tracks the pressure variations in real time.

When you stop speaking, the damping term is what causes the diaphragm to settle back to rest rather than ringing indefinitely.

This model has a natural resonant frequency — the frequency at which the system oscillates most vigorously when driven by an external force:

You've experienced resonance before: push a child on a swing at just the right rhythm and they soar; push at the wrong rhythm and you fight the motion. A diaphragm works the same way — frequencies near get amplified, while others don't.

Whether this resonance is a problem depends on the damping. Remember the term from the equation above? The ratio of damping to the critical threshold determines how the diaphragm behaves:

- Underdamped: the diaphragm rings like a struck bell, amplifying frequencies near . Cheap microphones often exhibit this — you hear it as a harsh, tinny coloration on voices or a brittle sibilance on "s" sounds.

- Overdamped: the diaphragm is sluggish, like pushing through honey. It can't keep up with rapid pressure changes, so high frequencies get rolled off and everything sounds muffled.

- Critically damped: the sweet spot. The diaphragm tracks the incoming pressure wave as faithfully as possible and settles back to rest without overshooting. This produces a flat frequency response — meaning the mic reproduces all frequencies at roughly equal sensitivity, without artificially boosting or attenuating any part of the spectrum.

In practice, well-designed microphones target critical or slightly overdamped behavior. A tiny bit of overdamping sacrifices negligible high-frequency response but adds a safety margin against resonant ringing — a worthwhile trade-off when the goal is accurate reproduction of the original sound.